Sanctuary 30th Anniversary Series – Blog #1 “Finding sanctuary: An idea comes to fruition” by Dan Haifley

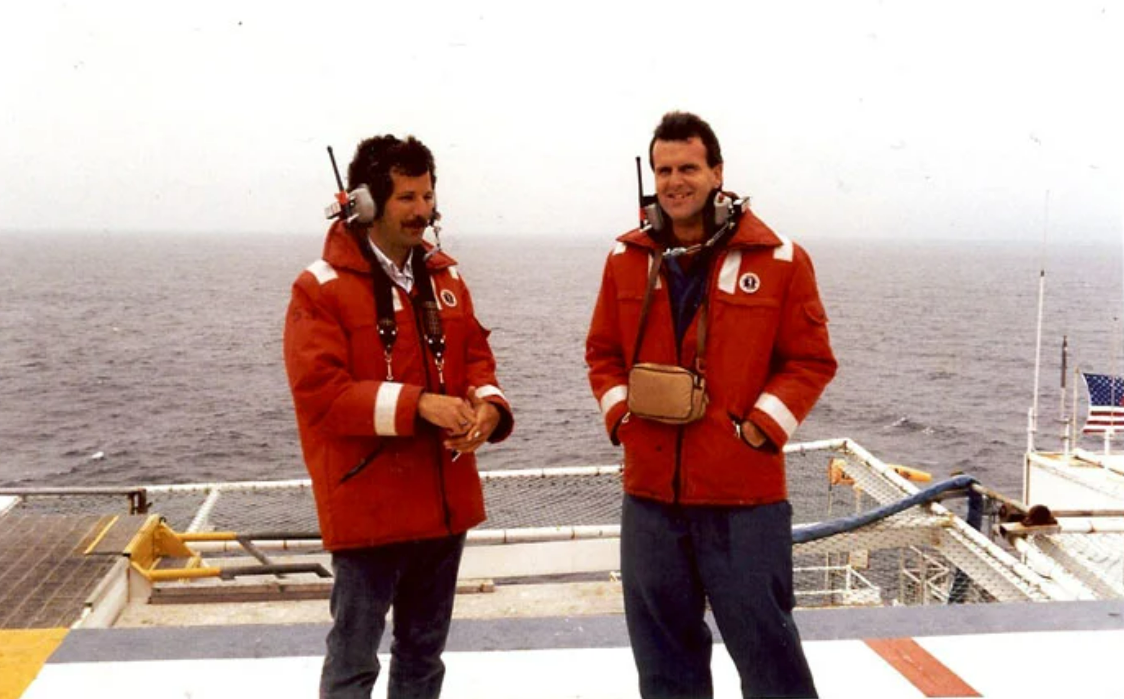

Dan Haifley and Don Lane on Platform Irene, offshore Santa Maria 1990. (Scott Kennedy/Contributed)

California’s beautifully complex coastline features rock outcroppings, sandy beaches, tide pools and wetlands. Parts of the coast are also defined by what we don’t see, such as offshore oil platforms. It was just three decades ago when waters between Santa Cruz and San Francisco were a high value target for federal energy planners and the oil industry.

But on Sept. 18, 1992, waters off one quarter of the state’s coast were designated as Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. It joined the west coast’s Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary off Washington, and Greater Farallones, Cordell Bank and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuaries off California, and hopefully it will be joined by future additions of the tribally nominated Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary off California and Alaĝum Kanuux̂ Marine Sanctuary off Alaska.

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary prohibits offshore oil extraction. Its team undertakes research, education and protection for productive waters that absorb excess carbon from climate change, produce oxygen, and support habitats for species including Blue whales, California sea otters, birds, invertebrates, deep sea creatures, fish and an adjacent human population. Its 6,094 square miles include Monterey Submarine Canyon that plunges 11,800 feet deep off Moss Landing, and Davidson Seamount, added in 2009, whose 7,500-foot-high summit is 4,000 feet below the surface, 75 miles west of San Simeon.

The reason for this monumental protection was a combination of science, leadership from Congressmember Leon Panetta, and a citizen movement demanding the largest boundary and strongest protections possible for the sanctuary that waged, in the words of retired Congressmember Sam Farr, a “bottoms-up, not a top-down” campaign.

Saving Our Shores

An organization named Save Our Shores helped to lead the campaign to secure the strongest protections, within the largest area thus far achieved, for the sanctuary. That effort built upon work done by citizens in the 1960s and 1970s to defeat a nuclear plant near Davenport and deep-water oil port at Moss Landing, and to convince California voters to approve the California Coastal Act in 1972. That same year, with the terrible televised images of the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill still fresh in their constituent’s minds, Congress approved a raft of environmental laws including one that established national marine sanctuaries.

Wall of defense against offshore oil

Before it stated to work on the marine sanctuary campaign, Save Our Shores encouraged coastal communities to enact laws restricting the development of onshore facilities necessary for offshore oil development, such as pipelines, helicopter pads and storage and staging yards. The federal government can lease the ocean floor for oil drilling from 3 to 200 miles offshore, and the state controls those rights from the mean high tide line out to 3 miles. But local governments retain zoning power within their own boundaries.

Frustrated with a federal process they believed was not responsive to local concerns, a unique strategy was conceived by Santa Cruz County Supervisor Gary Patton, Santa Cruz City Councilmembers John Laird and Mardi Wormhoudt, Save Our Shores’ Kim Tschantz, and others. They started with the City of Santa Cruz, where in 1985, 82% of voters voted to require that any zoning changes to accommodate such facilities must be approved by a vote of the electorate.

The measure also directed the city to help fund an effort to lead the fight against drilling off California’s coast. Save Our Shores, a posse of volunteers working on coastal protection since 1978, was tapped to take on that fight, and I was hired to coordinate it, with a budget of $15,000 to $25,000 per year. We went to work encouraging other communities to pass similar laws, either at the ballot box or by their governing body.

In spring of 1986 a letter from Santa Cruz Mayor Mike Rotkin was sent to cities and counties, with a copy of Santa Cruz’s ordinance attached. I made follow-up calls, then traveled the state in my Ford Pinto to make presentations from a slide show constructed on my kitchen table to local governments, sometimes with Mayor Rotkin and Councilmember John Laird, but most of the time alone, sleeping on couches in the homes of local activists or officials.

Ultimately, 26 cities and counties from San Diego to Humboldt approved such ordinances; most were passed by local voters by wide margins. Laguna Beach City Councilmember Robert Gentry referred to as a “wall of defense” against new offshore oil drilling. Others called it a seagrass rebellion.

Oil industry fights back

The oil industry took notice of the ordinances and responded in two ways. First, local governments were invited to visit an oil platform, and in 1990 Santa Cruz City Councilmembers Don Lane and Scott Kennedy went and took me along as “city staff.” Secondly, a lawsuit was filed against 13 of the 26 communities, who pooled their legal funds and hired Roger Beers, a San Francisco attorney.

The suit, filed by the Western Oil and Gas Association (now the Western States Petroleum Association) argued that local governments were interfering with interstate commerce — that the production, treatment and distribution of oil crossed state lines and was essential to power the U.S. economy. It landed in the Los Angeles courtroom of federal judge Consuela Marshall of the 9th District Court of Appeals, who ruled in favor of local governments. In January 1992, the Supreme Court declined to review that decision. The courts felt that the issues raised in the oil industry complaint were not “ripe” for consideration, since no city or county had yet closed the door on an onshore facility. That changed shortly thereafter, however, with San Luis Obispo County voters’ rejection of one.

Save Our Shores’ campaign was one component of the statewide effort to prevent offshore oil development. In my next installment, Congressmember Leon Panetta leads Congress in withholding funds and citizens fight oil lease sales, then pivots toward permanent protection.

Dan Haifley currently serves on the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Foundation board. He was director of Save Our Shores 1986-1993, and O’Neill Sea Odyssey from 1999-2019. He can be reached at dan.haifley@gmail.com. For more on the sanctuary’s 30th anniversary, go to montereybayfoundation.org.

About this series

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary celebrates its 30th anniversary this fall, and the national sanctuary system celebrates its 50th. For the next 12 weeks, the Sentinel will publish columns by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, along with Sam Farr, Dan Haifley, Fred Keeley, and Sanctuary Superintendent Dr. Lisa Wooninck. All of these contributors serve on the board of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Foundation and were involved with the Sanctuary’s designation.